He passed away with his eyes open, blue as the sky and big as his curiosity and his vital impetus; those wild and expressive eyes, vehement as he himself was, with quick and sharp words, but a tender heart. He died on March 28th 1942, the Saturday before Easter, in Alicante. But not completely, because whoever is eternal never disappears.

In Orihuela, his town and mine (2)

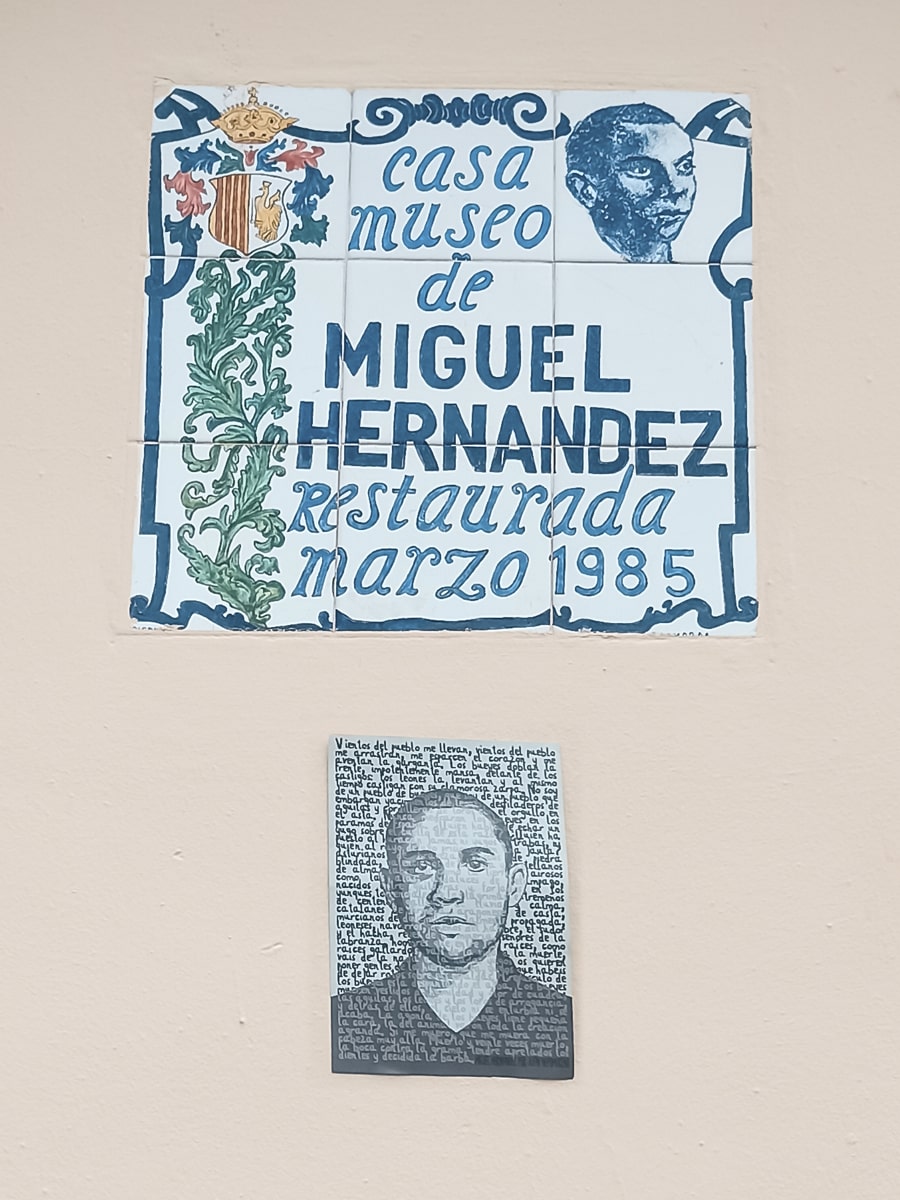

Son of Concheta and Miguel, a former watchman turned rancher who owned a large herd and sold cattle to Valencia and Barcelona, which gave him a certain position despite the fact that his family did not enjoy privileges of any kind. As a teenager, he received a scholarship to study at the Jesuit school of Santo Domingo in Orihuela. From the first moment he showed great intelligence and a mastery of language for which he won titles and accolades. But his father decided that, at 15 years of age, his knowledge was enough, and took him away from his studies to take care of a herd of goats. Far from settling down, Miguel continued to train during the following years on his own and with the help of the clergyman Luis Almarcha and under the influence of his friend José Marín.

Miguel and Marín met through their friend, a baker and poet, Carlos Fenoll. Marín was younger, bourgeois, sickly, studious and deeply Catholic. He soon developed the pseudonym by which he would be known: Ramón Sijé (anagram of his own name). Living in such a conservative and oppressive environment, and with such powerful influences, the first poetic productions of the young Miguel Hernández could only have a marked religious sign. He tried to escape from this in his first book: Perito en lunas (1933), which caused his first estrangement from Sijé.

After several unsuccessful attempts in which he made contact with important figures of the literature of the time such as José Bergamín or Federico García Lorca (with little success), Miguel settled in Madrid definitively in 1935. Once there, he struck up friendships with figures as important as Pablo Neruda, Vicente Aliexandre (both received the Nobel Prize for Literature years later), the philosopher María Zambrano or the surrealist plastics artists of the Vallecas School. Reinforced by these new friendships, he strengthened his pantheistic beliefs and his rejection of Catholic indoctrination, increasing his social vocation. Sijé, for his part, took the opposite path, exaggerating his Catholicism and remaining even in a more radical position than the fascist movements that were booming at the time.

During the following months, Miguel got a good job at the Espasa-Calpé Publishing house as editor of the bullfighting encyclopedia, under the command of José María de Cossio, a renowned Falangist who, however, was his great friend and helper. With the support and influence of Aleixandre and Neruda, Miguel finds his own path and, far removed from his Orihuela Catholic past, writes El Rayo que no Cesa. This collection of poems became the greatest exponent of the Hernandian worldview (life-love-death), in it he fully exploited his mastery of learned poetic forms and confirmed him as one of the most important figures in contemporary poetry. Shortly before its publication, on Christmas 1935, Sijé died of an unknown illness. Both were irreconcilably distant, but Miguel wrote Elegía, a poem in a style opposed to that defended by Sijé, but which served to immortalize him.

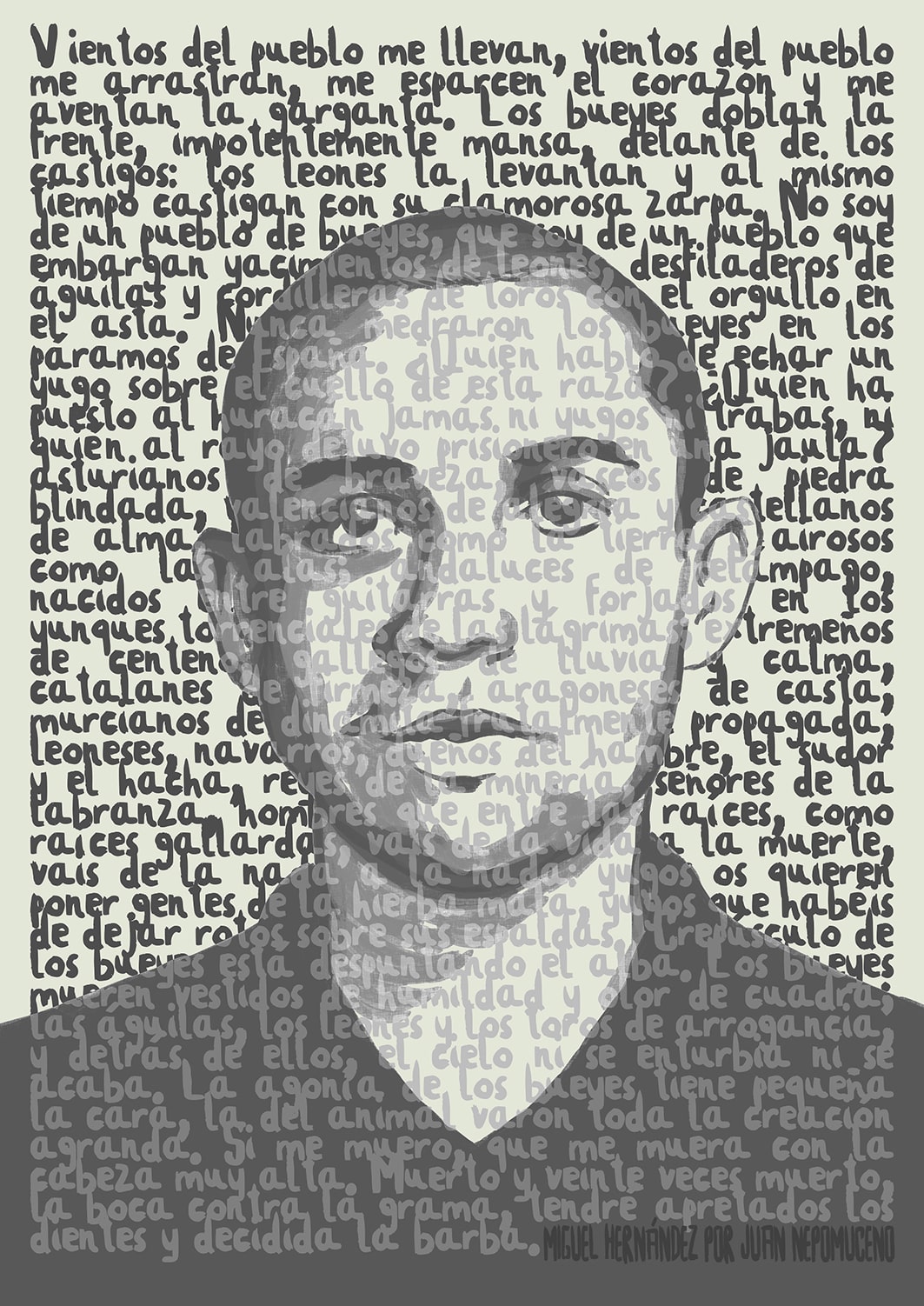

"We poets are the wind of the people"

When the fascist uprising took place in the summer of 1936, which marked the beginning of the Spanish civil war, Miguel was in Madrid, working for the bullfighting encyclopedia. Months before, he had enrolled in the Pedagogical Missions of the Second Spanish Republic (an educational project that aimed to bring culture to disadvantaged rural areas). During his stay in Madrid, he had developed his class consciousness, reinforced by his origins, and after suffering several violent episodes by the Civil Guard, he had joined the Communist Party a few months before the outbreak of the war, sponsored by the poets Rafael Alberti and Maria Teresa Leon.

Despite being a literary character of proven influence in the cultural world of the time, and a member of the Alliance of Antifascist Intellectuals, conscientiously faithful to his humble principles, he decided not to abuse his privileged position and enlisted as an anonymous volunteer in the 5th Regiment of the popular republican militias, leaving for the front in Toledo and Extremadura and working as a sapper digging ditches. When the word spread that the poet was in such tasks, he was called to occupy positions of greater relevance and more in line with his intellectual capacity, being appointed Military Political Commissioner and employed in propagandistic tasks, a performance that led him to serve in Andalusia and Teruel. It was at that time when his urgent war poetry flowed and Viento del pueblo (Wind of the People) was born, a book committed to those who suffered the most on the front lines of battle, with whom he felt most identified.

After returning from his diplomatic trip to the USSR as part of the committee of republican intellectual representatives and his tour of Europe in the autumn of 1937 (in Paris, the Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier made the only voice recording that is preserved of the poet), the pessimism of Miguel about the war increased. He felt that the European nations had abandoned Spain to its fate, and saw the Republican defeat as imminent. His health accused him, worsening old lung and brain ailments, and the death of his son Manuel Ramón, his first son with Josefina, when he was only ten months old only accelerated the evolution of a poetry that focused more on denouncing injustices and the situation of the weakest than in the propagandist work that had previously occupied him. These events gave birth to El hombre acecha, a book that was printed but not published at the end of the civil war and that became an early sample of social poetry.

Santiago Álvarez, a commissioner of the 5th Regiment of which Miguel was part of, said of him that he was not like Alberti or other poets and intellectuals who went to the front, attended an event and returned to Madrid. "He was there all the time, like one more combatant. What happens is that he was an exceptional poet." And, indeed, without detracting from the adherence to the republican cause of other contemporary authors, none can be equal in commitment and fidelity to the principles of him to Miguel Hernández. Most of his companions did not have time to go into exile from the defeated Spain, in all his rights. But few did anything to help him get to safety. It is also the result of his ingenuity and well-thought-out humanity, he himself insisted on returning to Orihuela with his family, where he was arrested and tortured before the indulgence of the same people who had been his countrymen years ago. Hatred was muffled behind the windows. (3)

Dead and twenty times dead (4)

In an ironic and disastrous way, 31 years ended up being the time he lived in this always hostile land where he never found the accommodation he deserved. The pressures from the ecclesiastical establishment (headed by his former supporter Luis Almarcha in the role of Franco's supreme inquisitor) to renounce the rights to his work in exchange for the commutation of his sentence were unsuccessful, Miguel always remaining faithful to his principles.

A few days before his death, he contracted a Catholic marriage with Josefina, with the purpose of ensuring for her and Manuel Miguel (his second son) the legal rights of his work, the only legacy he could leave them, being part of it Cancionero y romancero de ausencias (Songs and Ballads of Absence), written in prison, unfinished and published in Argentina in 1958. On March 28th 1942, at half past five in the morning, almost three years after the end of the civil war and after more than two in captivity, Miguel Hernández died in the Reformatory of adults in Alicante, the last of the destinations in his particular martyrdom.

Miguel died for Spain and prison, condemned and tortured by those who were his judges, executioners and jailers; he also died due to forgetfulness and abandonment of a few others who, even being on the same side, preferred to look to another when they could have done something else. He died of typhus, tuberculosis, hyperthyroidism and many other lung and brain ailments that accompanied him throughout his short life of 31 years. But also, in part, imprisoned by his own pride, obstinacy and principles. His last act of rebellion, once dead, was to be mistakenly buried feet first in niche 1009 of the Alicante cemetery, a ritual reserved for ecclesiastics. Dead and twenty times dead, gritted teeth and determined beard.(4)

I bleed, I fight, I live (5)

In short, over the last few months I have done a great deal of compilation on so many fronts with the sole intention of doing my bit to keep the memory of Miguel Hernández alive. The main inspiration and source of information has been the biography of the poet written by José Luis Ferris and called "Miguel Hernández: pasiones, cárcel y muerte de un poeta” (Miguel Hernández, passions, prison and death of a poet). Also the graphic novel "Piedra viva", by Román López Cabrera and Marina Armengol Más, but also the studies and publications of other authors. My only wish is to pass on at least a little bit of the passion I feel for Miguel Hernández. I hope you like it so much that you want to know more and share how much I have shown you here.

Allí yo mucho tiempo,

Notes:

2 Comentarios

Laura Montoya

3/4/2022 16:49:15

Juan, como siempre, un sentimiento único, elegante, poético. ❤️

Responder

3/4/2022 17:13:32

Thank you for your help 😘😊

Responder

Tu comentario se publicará después de su aprobación.

Deja una respuesta. |

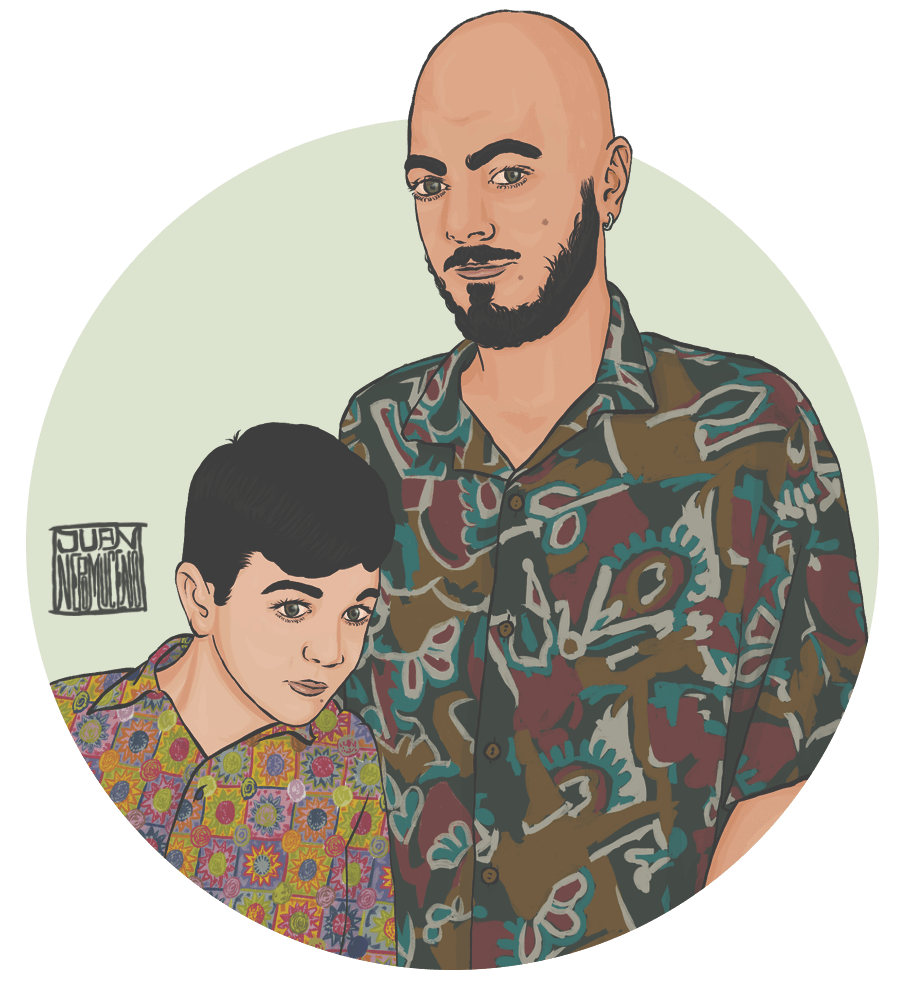

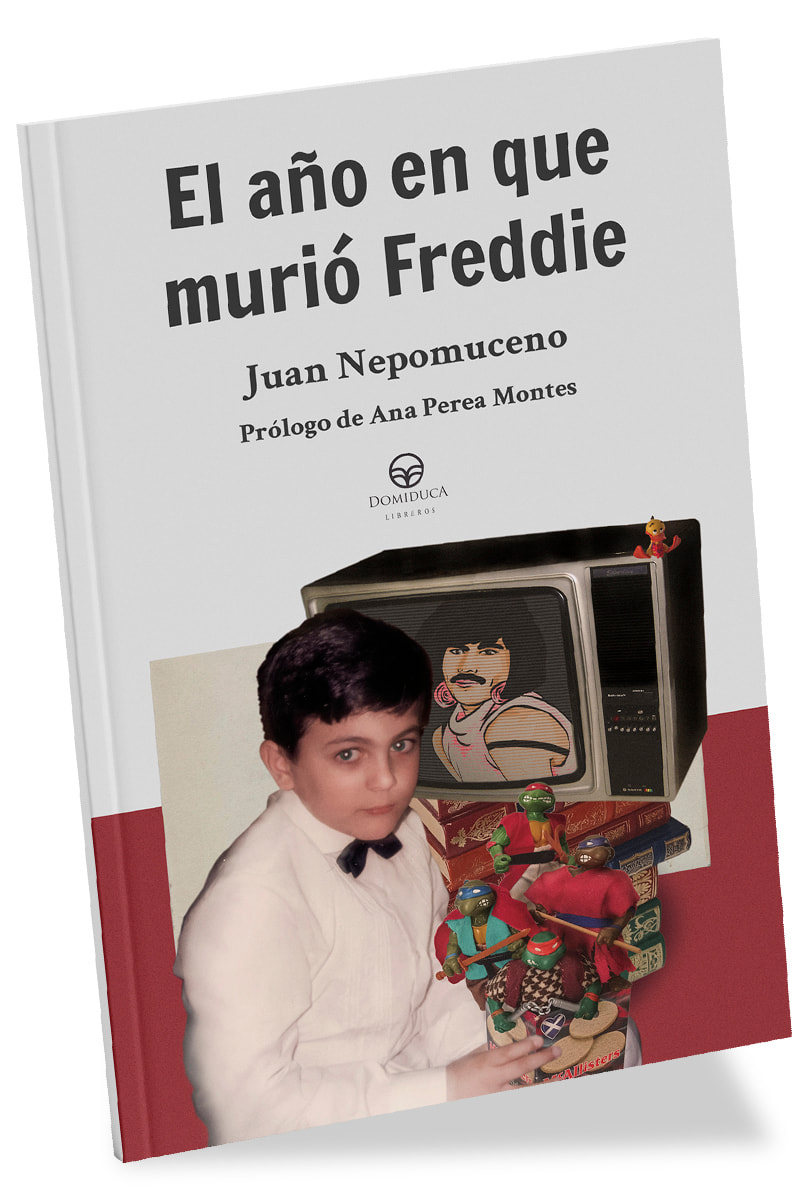

Juan NepomucenoArte digital, pintura e ilustración, diseño gráfico, murales... Me dedico a todo esto... y a mucho más. Llega "El año en que murió Freddie" mi primer libro de la mano de Domiduca Libreros. ¡No te quedes sin él"

MI NEWSLETTER

La estantería

Junio 2024

Las etiquetas

Todo

"Deja de pensar, deja que todo fluya, siéntate al sol y disfruta de la vida."

|